An author reflects: "The choking dog years"

The riveting first instalment of The Origin Story for my new book

When I was a music critic, one of the questions that I hated to ask, but often felt compelled to ask, was the old reliable: “Who were your influences?”

Since the publication of my new book, Getting Unstuck: Seven Transformational Practices for Golf Nerds, a few people have asked what most influenced me in writing my first book that you might say is “personal.” That is, it’s the first book that I wrote as a coach and golfer rather than as a journalist trying to capture other people’s experiences.

My next three newsletters on Substack are my attempt to describe my influences in writing the book, or what’s called in the business: my origin story.

During every round, I think about my late father Dennis at least once. I’ll find myself repeating one of his golf aphorisms, such as “the golf gods giveth and taketh away, although they mostly taketh.” Or I’ll remember something that happened on the golf course, usually at Sunningdale Golf & Country Club in London, Ontario where we were members and I played and caddied as a junior.

I basked in warm nostalgia a few weeks ago when—for the first time in about 12 years—I played Sunningdale. My companions were writer Ted McIntyre, an old friend since the 90s when I was a golf writer, and golf architect Doug Carrick, who renovated the course and designed six new holes. Poor guys. I regaled them with a story on just about every hole.

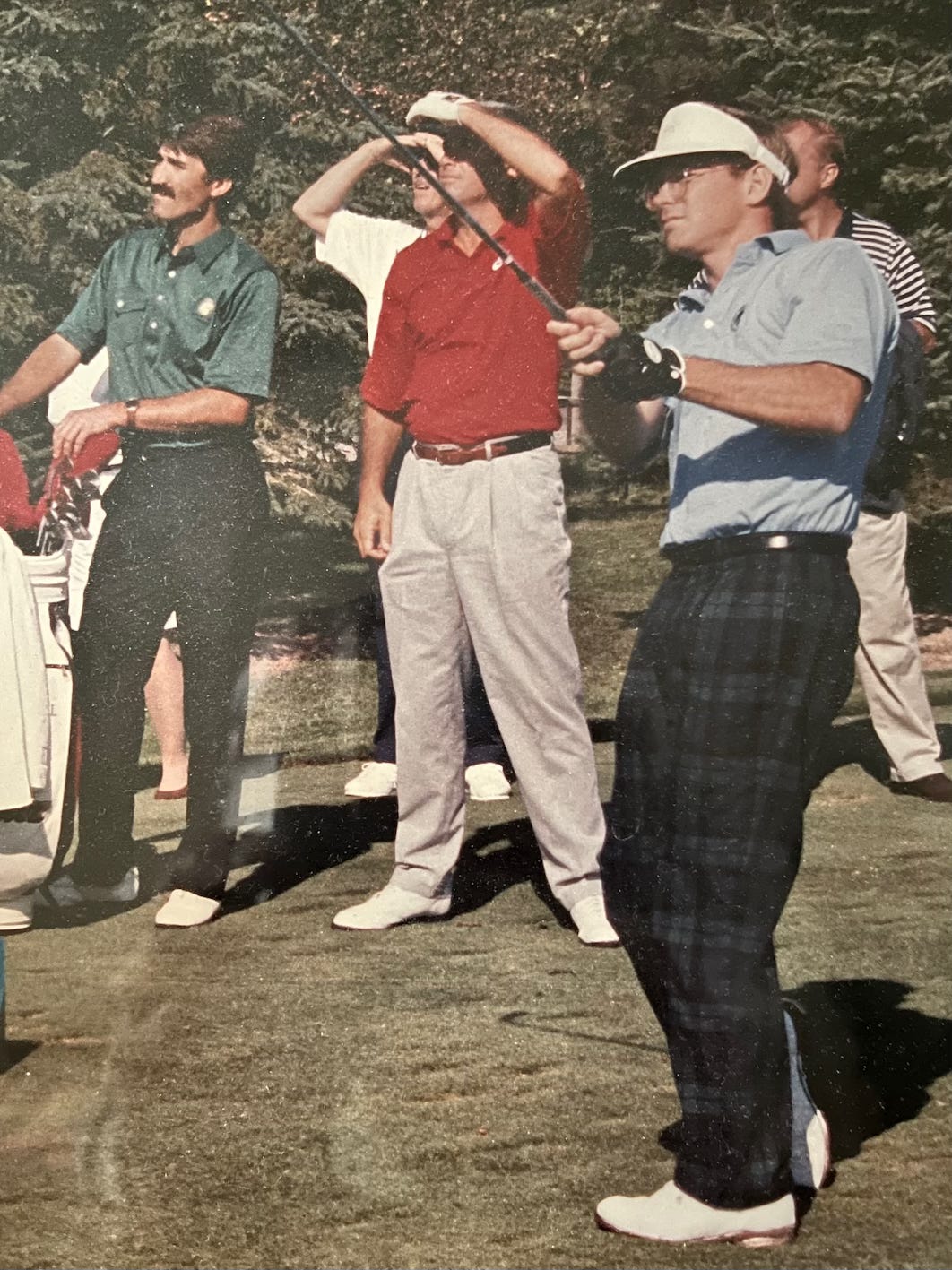

Among the stories was how I excitedly returned a few times every season to play on a Saturday morning with Dad and his buddies. I was always nervous; anxious to show him and his pals—to whom he bragged about his son, the golf writer—that I was indeed a player.

I was so tight you couldn’t ram a nail up my butt with a hammer. I rode an emotional roller coaster, and usually choked my guts out. I’m embarrassed to admit it, but I lived and died—mostly died—with the quality of my golf. I sulked and dragged my carcass around the course like I was headed to the gallows.

As a young man, I didn’t have the perspective that while my father certainly hoped I’d play well, for him it was mainly about sharing time, his club, his friends and the game we loved.

More than a few times early in the back nine Dad would try to cheer me up and say, “Hey pal, let’s have fun.” Being an arrogant know-it-all whippersnapper, I would dismiss this as more of his unwanted fatherly advice.

I thought: “For God’s sake, I write about the game!” I continued to play with painstaking deliberateness only to hit the ball into oblivion, which often prompted him to say, “Let’s see your Don’t-give-a-shit swing.”

Fuming, and with nothing to lose, I’d swing away freely and—pretty well every time—nail a beauty straight down the pike. I think Dad’s don’t-give-a-shit-swing suggestion was a crude forerunner of “stay out of your own way.”

Like the golfer who suffers a disastrous front nine, I’d often play much better on the back, thanks to Dad’s intervention. But during my next game with him or my friends, I’d be right back to my old behaviour—trying to swing with perfection.

In golf—like everything that I was invested in—I was a seeker, forever searching for expert information, the undiscovered secrets, the sacred mysteries. As a golf writer, I chased information from tour players and their coaches that I hoped would make me better.

I craved being a scratch player like the club champions I caddied for as a kid. I wanted their swagger and confidence to paint the sky and putt like gods.

But … I was stalled around 9-10 handicap, which is better than most, but I felt like I was mediocre, chronically frustrated. Stuck.

While sitting in press rooms at tournaments, it started to dawn on me that tour players rarely talked about their swing mechanics; instead, they usually talked about their thinking, strategy, decisions, reactions, and focus—elements of what they called the “mental game.”

I started to look at books on “sports psychology” and began to appreciate the mental skills of champions such as Ben Hogan, Jack Nicklaus, Nick Faldo, Betsy King and Annika Sorenstam.

Conversely, I could see parts of myself in portraits of under-performing performers, especially famous “chokes” such as Doug Saunders in the 1970 Open Championship, Scott Hoch in the 1989 Masters, or baseball player Bill Buckner in the 1986 World Series. (I didn’t provide links because these guys don’t need more piling on.)

I came to this conclusion: It wasn’t my golf swing that was the problem.

I was a self-interfering paralysis-by-analysis basket case. (The mental game books say go easy with the self-talk, so obviously I had a long way to go.)

The path to enlightenment and a choke-free golf game was now obvious—learning about the mental game would be my salvation.

So, I did what I do—I sought as much information as I could about the “mental game,” devouring books, magazine articles, video tapes, CDs and DVDs. (This was just before the explosion of online content.)

To be continued …

Along with Getting Unstuck, I’m also the author of The Feeling of Greatness: The Moe Norman Story, and co-host of the Swing Thoughts podcast.

If you’re interested in golf coaching—including on the mental part of your game—please send an email to tim@oconnorgolf.ca. I invite you to check out www.oconnorgolf.ca.

Sim Weekly

Dive into the world of indoor golf with Sim Weekly. From setting up your perfect home sim and getting expert installation tips, to in-depth product reviews and practical advice for honing your skills at home, we’ve got you covered. Plus, enjoy fun content, exclusive giveaways, and more. Join 1k+ golfers elevating their indoor game.