Even when we’re not working, we’re working.

Almost every person I know is always working on something—to improve their golf swing, or on becoming less angry, or more peaceful. Or on making more money. Or living with less.

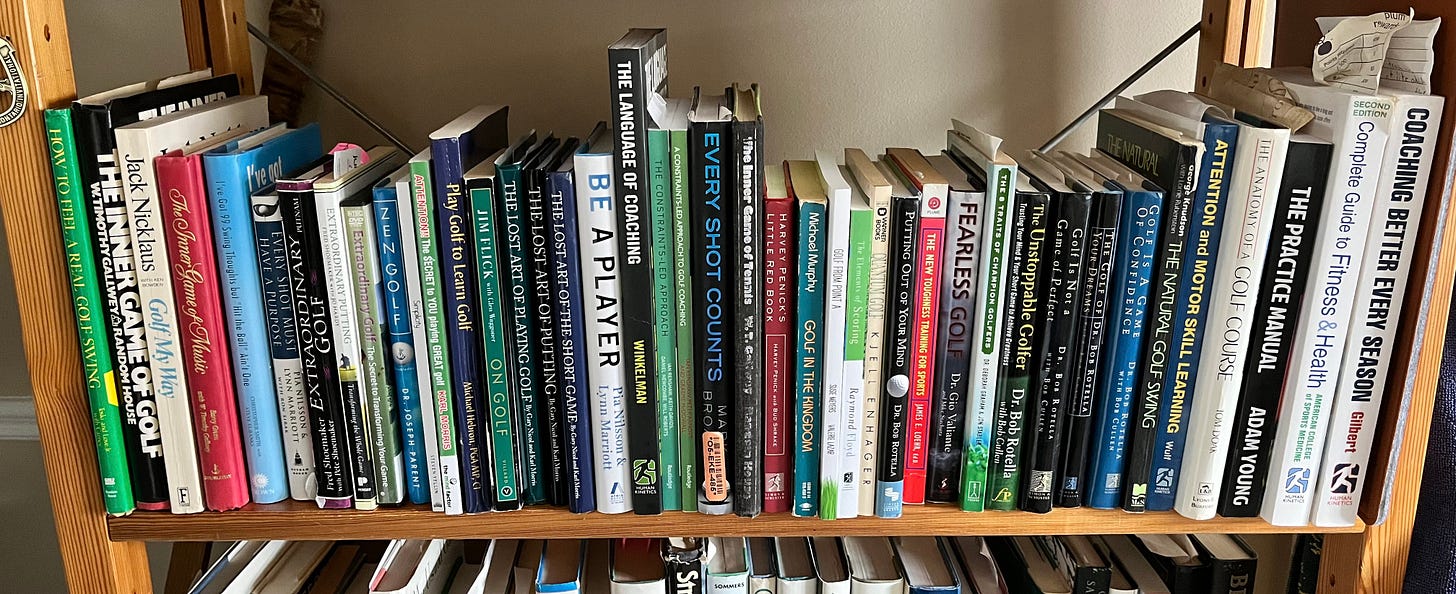

I’m guilty. I’m definitely a seeker. My wife thinks that I will die—metaphorically at least—when the giant stack of books on my bedside table falls over one night and crushes me.

I’m sure you have a friend who is always taking golf lessons and sweating it out on the range; or a friend who is always on some kind of cleanse, or taking up a new practice.

I know a guy who, I swear, has gone on every men’s retreat a man can go on. And he’s still just as messed as I am.

I have read hundreds of golf instruction books on every part of the game, and tried my darnedest to put their wisdom to work. Am I a better golfer for reading them? The answer is a big fat—marginally.

Consider all the books you’ve read to improve your golf or whatever you’ve wanted to do with your career, our life, your annoying habits.

It leads me to ask: Does all this work we do … actually work?

If we’re honest, talk about poor ROI.

Do self-help books actually help?

Could there be a better way to work on ourselves?

Ariel and Shya Kane think so. They make their case in a book with the funniest title I’ve ever seen for a book that you find in the self-help section: Working On Yourself Doesn’t Work.

Like many golfers and seekers, they have read a gazillion books, and taken dozens of courses. They became so bent on developing themselves that they sold their worldly goods and their New York apartment and traveled the world.

But after a few years and yet another extended retreat, they asked themselves: Have we changed?

Not really.

Were they happy? Sometimes. Fleetingly.

They deduced that working on yourself doesn’t work.

It’s a broad-brush stroke. I wonder if they are over-stating the case. But I believe that the book provides some insight into why our desire for change often feels desperate and ultimately leaves us dissatisfied.

In making their case, the Kanes say that we rely almost exclusively on thinking in our efforts to decide on our goals and the actions we will take.

‘Well, of course,’ you might think. ‘We have to be logical.’

The gold standard—my phrase, not the Kanes’—for considering a serious course of action to carefully evaluate the facts, options and risks, and our needs. We might write out a pros and cons list, or perhaps even do a SWOT analysis. Then we decide.

However, the track record for the gold standard is spotty, the Kanes argue.

But how can logic fail us? Isn’t it important to make decisions based on ‘reality’ without being deluded by emotions or mental nonsense?

Our minds mean well, but …

Let’s start by looking at where everything starts—the brain. The main job of the brain is to keep us alive. The mind does everything in its power to protect us. As we go through life, especially when we’re children, our minds fixate on the bad stuff that happens to us. Our minds act like Negative Nellies that try to protect us from suffering more bad stuff.

Our past experiences are the greatest influence on our thinking and behaviours.

The Kanes argue that our decisions are usually based on patterns of thinking that we have habitually engaged in since we were kids. “Would you seriously ask a two-year-old what you should do, and live your life based on that advice?” they ask.

So the Kanes say that rather than make a decision—that is, rely exclusively on thinking—you’re better off making a choice.

“A choice is a selection that is reflective of your heartfelt desires or authentic wishes,” they write. “A choice takes the pros and cons into consideration, but then allows for an intuitive leap.”

What I deduced from the Kanes was this: We don’t need to abandon the gold standard, or rely exclusively on our gut. Rather, we need to do the heavy lifting, and then relax and see what happens.

This aligns with a practice that the Jesuit order of Roman Catholic priests call spiritual discernment. The Jesuits and many of their followers use discernment in making decisions, and choosing the direction of their lives.

In The Ignatian Adventure, Fr. Kevin O’Brien writes that discernment involves becoming aware of our “interior movements,” which includes thoughts, imaginations, and emotions.

This can include doing our due diligence, researching, writing out pros and cons, and so on. But after we’re done all that, we discern. That is, “we reflect on those interior movements to determine where they come from and where they lead us,” O’Brien writes.

Discernment strikes me as similar strategy used by author Stephen King. In On Writing, King says that when he gets muddled in writing a story, he’ll often stop working and thinking about it. He then gives it over to “the boys in the basement.” He uses that term to describe his subconscious mind, which is intelligent, creative and beyond his control.

The boys in the basement

He’ll perhaps go for a walk, do something else for the rest of the day, or just leave it over to the next day. Invariably, he finds that the boys in the basement come up with something that works.

I find it’s the same with golf; when I get out of the way, the boys in the basement do a very nice job of swinging the club, hitting a chip on line, or stroking the ball to the hole.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve become more aware that relying overly on stinking thinking causes self-interference, and leads to decisions that may not serve me. I’m not alone in this.

This has helped me to gain a greater understanding on why I have not achieved many goals that I’ve set in life. One stands out particularly.

Some context first; throughout my life, I chronically worried whether I would make enough money. My father struggled in the early days of his business career, so I’m thinking it started there.

In the early 90s, I was making top-scale at a news agency. But I wanted to become a freelance golf writer. Everything I heard and read said freelancing was a tough way to make a living. I was depressed for two years until I finally went for it. The choice was to stay miserable.

Within two years, I was making more money as a freelancer. I wrote for golf magazines around the world, I wrote three books, hosted radio shows, reported from the Masters for CBC Radio, and produced radio documentaries. I was golf columnist for the Financial Post daily newspaper; it was my anchor gig.

It was a wonderful time of my life; our sons Corey and Sean were born, we lived a cosmopolitan life in Toronto and then rented a house in the country.

But in 1998, The Financial Post was purchased and rolled into The National Post. I was not engaged as the golf writer. Without my anchor gig, I was now consumed with worry about supporting the family. Being passed over also shook my confidence as a writer.

I went on a personal retreat to plot my future. After a couple of days, I came up with a goal that I’d start a public relations consulting company in the golf business and develop it into a thriving agency. I’d eventually sell the agency, buy a big house on a hill overlooking a lake, and play lots of golf.

I did well as a consultant, working with organizations such as Nike Golf Canada, ClubLink Corporation, PGA of Canada, and Rogers. I engaged interns, part-time people, and sub-contracted. I made pretty good money.

But after 14 years, I had not built an agency. I was a loner consultant. After the 2008 recession, I lost my mojo for the business.

Gradually, it dawned on me: I never wanted to develop a PR agency.

At the time of my retreat, it made sense. A of media people went, as we said, to the dark side to make “real money.” I fell in love with the idea of developing an agency and that it would solve my immediate money worries and eventually make me a financial success.

The past is the past. Every now and then, I think that maybe the consulting thing was just a practical way of supporting my family, but there’s a part of me that believes I made a poor decision that was influenced by scarcity thinking.

So what am I doing now? I’ve taken a deeper dive back into writing with these blogs—or what Substack calls newsletters—and I’m writing some new books. I’m in my eighth year of the Swing Thoughts podcast, which is just radio on the internet.

In high school, I fancied myself as a writer and a teacher, which may explain why I’m also a coach now. I just always wanted to do these things. You could say I chose to do them.

As I get older, I’m finding that I’m putting more trust in the boys in the basement.

I don’t think they’ll ever help me move into a house on a hill, but it beats working.

Hi Peter:

Many thx for your note. That's incredible that you help support gamblers. That is such a gift that you are giving. Given that work you do, I can understand your sense that there might be a something at work in your golf. It's pretty damn cool what can happen when we get out of the way. You are indeed rich and important enough. In fact, we all are. Thx again and be well.

Spot on. I'm a retired 67yo golfing addict (my wife's label). 20 years ago I was a gambling addict (my label) & still do a lot of mentoring & support work with Gamblers Anonymous. I recently had a very emotionally taxing week that left me totally drained. I went out and shot 83 - my lowest competition round for 40 years - with someone else swinging the club (Higher Power?) Excess conscious thought can be a road block in so many areas of life. When I stopped trying to become rich and important, I became rich enough and important enough. Let go & let god.